7. Accessing data¶

7.1. Overview¶

The data stores are a key component in the application framework. All data which comes from persistent storage, or which is transferred between algorithms, or which is to be made persistent must reside within a data store. In this chapter we use a trivial event data model to look at how to access data within the stores, and also at the DataObject base class and some container classes related to it.

We also cover how to define your own data types and the steps necessary to save newly created objects to disk files. The writing of the converters necessary for the latter is covered in Chapter 13.

7.2. Using the data stores¶

There are four data stores currently implemented within the Gaudi framework: the event data store, the detector data store, the histogram store and the n-tuple store. Event data is the subject of this chapter. The other data stores are described in chapters Section 9 and Section 10 and Section 11 respectively. The stores themselves are no more than logical constructs with the actual access to the data being via the corresponding services. Both the event data service and the detector data service implement the same IDataProviderSvc interface, which can be used by algorithms to retrieve and store data. The histogram and n-tuple services implement extended versions of this interface (IHistogramSvc, INTupleSvc) which offer methods for creating and manipulating histograms and n-tuples, in addition to the data access methods provided by the other two stores.

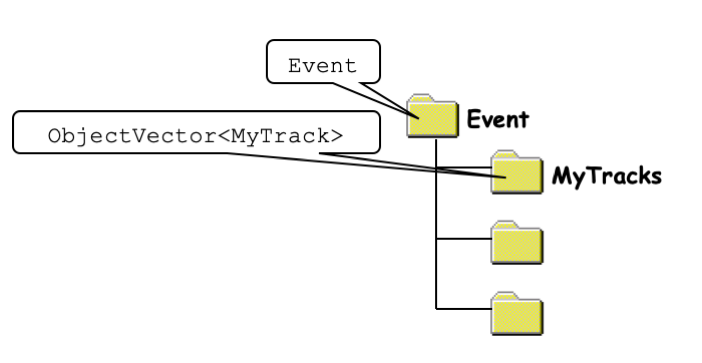

Only objects of a type derived from the DataObject base class may be placed directly within a data store. Within the store the objects are arranged in a tree structure, just like a Unix file system. As an example consider Fig. 7.1 which shows the trivial transient event data model of the RootIO example. An object is identified by its position in the tree expressed as a string such as: “/Event”, or “/Event/MyTracks”. In principle the structure of the tree, i.e. the set of all valid paths, may be deduced at run time by making repeated queries to the event data service, but this is unlikely to be useful in general since the structure will be largely fixed.

Fig. 7.1 The structure the event data model of the RootIO example¶

Interactions with the data stores are usually via the IDataProviderSvc interface, whose key methods are shown in Listing 7.1.

The first four methods are for retrieving a pointer to an object that is already in the store. How the object got into the store, whether it has been read in from a persistent store or added to the store by an algorithm, is irrelevant.

The find and retrieve methods come in two versions: one version uses a full path name as an object identifier, the other takes a pointer to a previously retrieved object and the name of the object to look for below that node in the tree.

Additionally the find and retrieve methods differ in one important respect: the find method will look in the store to see if the object is present (i.e. in memory) and if it is not will return a null pointer. The retrieve method, however, will attempt to load the object from a persistent store (database or file) if it is not found in memory. Only if it is not found in the persistent data store will the method return a null pointer (and a bad status code of course).

Navigation through the tree stucture of the data store is possible via the IDataManagerSvc interface of the data service, as described for example in http://cern.ch/lhcb-comp/Frameworks/Gaudi/Gaudi_v9/Changes_cookbook.pdf.

7.3. Using data objects¶

Whatever the concrete type of the object you have retrieved from the store the pointer which you have is a pointer to a DataObject, so before you can do anything useful with that object you must cast it to the correct type, for example:

The typedef on line 1 is just to save typing: in what follows we will use the two syntaxes interchangeably. After the dynamic_cast on line 10 all of the methods of the MyTrackVector class become available. If the object which is returned from the store does not match the type to which you try to cast it, an exception will be thrown. If you do not catch this exception it will be caught by the algorithm base class, and the program will stop, probably with an obscure message. A more elegant way to retrieve the data involves the use of Smart Pointers - this is discussed in section Section 7.8.

The last two methods shown in Listing 7.1 are for registering objects into the store. Suppose that an algorithm creates objects of type UDO from, say, objects of type MyTrack and wishes to place these into the store for use by other algorithms. Code to do this might look something like:

Once an object is registered into the store, the algorithm which created it relinquishes ownership. In other words the object should not be deleted. This is also true for objects which are contained within other objects, such as those derived from or instantiated from the ObjectVector class (see the following section). Furthermore objects which are to be registered into the store must be created on the heap, i.e. they must be created with the new operator.

7.4. Object containers¶

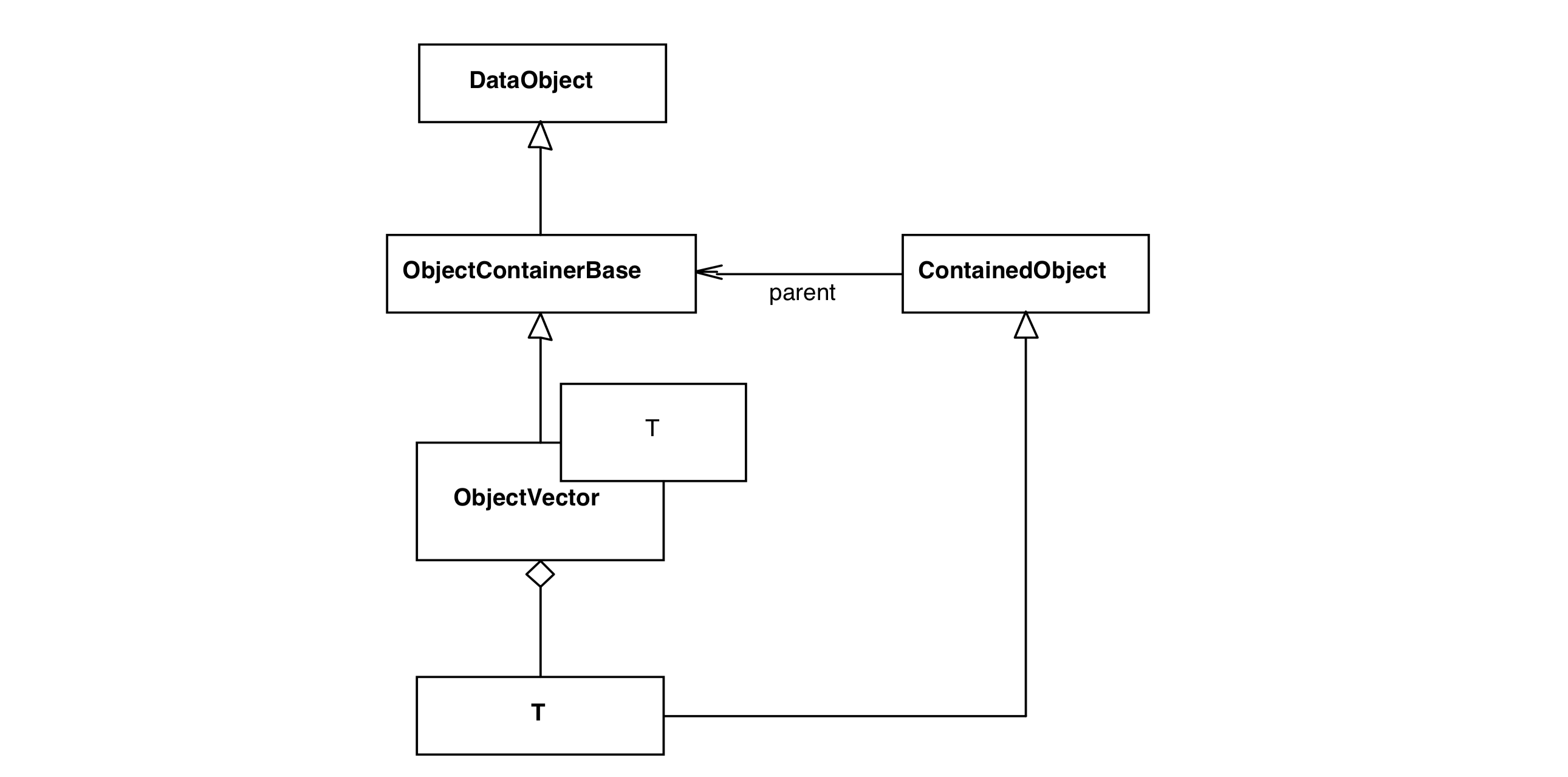

As mentioned before, all objects which can be placed directly within one of the stores must be derived from the DataObject class. There is, however, another (indirect) way to store objects within a store. This is by putting a set of objects (themselves not derived from DataObject and thus not directly storable) into an object which is derived from DataObject and which may thus be registered into a store.

An object container base class is implemented within the framework and a number of templated object container classes may be implemented in the future. For the moment, two “concrete” container classes are implemented: ObjectVector<T> and ObjectList<T>. These classes are based upon the STL classes and provide mostly the same interface. Unlike the STL containers which are essentially designed to hold objects, the container classes within the framework contain only pointers to objects, thus avoiding a lot of memory to memory copying.

A further difference with the STL containers is that the type T cannot be anything you like. It must be a type derived from the ContainedObject base class, see Fig. 7.2. In this way all “contained” objects have a pointer back to their containing object. This is required, in particular, by the converters for dealing with links between objects. A ramification of this is that container objects may not contain other container objects (without the use of multiple inheritance).

Fig. 7.2 The relationship between the DataObject, ObjectVector and ContainedObjec classes¶

As mentioned above, objects which are contained within one of these container objects may not be located, or registered, individually within the store. Only the container object may be located via a call to findObject() or retrieveObject(). Thus with regard to interaction with the data stores a container object and the objects that it contains behave as a single object.

The intention is that “small” objects such as clusters, hits, tracks, etc. are derived from the ContainedObject base class and that in general algorithms will take object containers as their input data and produce new object containers of a different type as their output.

The reason behind this is essentially one of optimization. If all objects were treated on an equal footing, then there would be many more accesses to the persistent store to retrieve very small objects. By grouping objects together like this we are able to have fewer accesses, with each access retrieving bigger objects.

7.5. Using object containers¶

The code fragment below shows the creation of an object container. This container can contain pointers to objects of type MyTrack and only to objects of this type (including derived types). An object of the required type is created on the heap (i.e. via a call to new) and is added to the container with the standard STL call.

ObjectVector<MyTrack> trackContainer; MyTrack* h1 = new MyTrack; trackContainer.push_back(h1);After the call to push_back() the MyTrack object “belongs” to the container. If the container is registered into the store, the hits that it contains will go with it. Note in particular that if you delete the container you will also delete its contents, i.e. all of the objects pointed to by the pointers in the container.

Removing an object from a container may be done in two semantically different ways. The difference being whether on removal from a container the object is also deleted or not. Removal with deletion may be achieved in several ways (following previous code fragment):

trackContainer.pop_back(); trackContainer.erase( end() ); delete h1;The method pop_back() removes the last element in the container, whereas erase() maybe used to remove any other element via an iterator. In the code fragment above it is used to remove the last element also.

Deleting a contained object, the third option above, will automatically trigger its removal from the container. This is done by the destructor of the ContainedObject base class.

If you wish to remove an object from the container without destroying it (the second possible semantic) use the release() method:

trackContainer.release(h1);Since the fate of a contained object is so closely tied to that of its container life would become more complex if objects could belong to more than one container. Suppose that an object belonged to two containers, one of which was deleted. Should the object be deleted and removed from the second container, or not deleted? To avoid such issues an object is allowed to belong to a single container only.

If you wish to move an object from one container to another, you must first remove it from one and then add to the other. However, the first operation is done implicitly for you when you try to add an object to a second container:

container1.push_back(h1); // Add to fist container container2.push_back(h1); // Move to second container, internally invokes release()Since the object h1 has a link back to its container, the push_back() method is able to first follow this link and invoke the release() method to remove the object from the first container, before adding it into the second.

In general your first exposure to object containers is likely to be when retrieving data from the event data store. The sample code in Listing 7.3 shows how, once you have retrieved an object container from the store you may iterate over its contents, just as with an STL vector.

The variable tracks is set to point to an object in the event data store of type: ObjectVector<MyTrack> with a dynamic cast (not shown above). An iterator (i.e. a pointer-like object for looping over the contents of the container) is defined on line 3 and this is used within the loop to point consecutively to each of the contained objects. In this case the objects contained within the ObjectVector are of type “pointer to MyTrack”. The iterator returns each object in turn and in the example, the energy of the object is used to fill a histogram.

7.6. Data access checklist¶

A little reminder:

· Do not delete objects that you have registered.· Do not delete objects that are contained within an object that you have registered.· Do not register local objects, i.e. objects NOT created with the new operator.· Do not delete objects which you got from the store via findObject() or retrieveObject().· Do delete objects which you create on the heap, i.e. by a call to new, and which you do not register into a store.

7.7. Defining Data Objects¶

If you want to create a new data object in the transient or persistent stores of Gaudi, you will have to define the structure of this object. This structure will be defined by C++-classes. These classes in general look very similar to each other; mainly they define the members of the class, which are either data values or which point to another class (eg. via a Smart Reference - see Section 7.9). For each of these members there is usually a set- and a get-method and some more stuff for the Smart Reference Vectors.

The writing of these classes is a tedious task and having to write this redundant information many times, of course, also bears the risk of many unnecessary typos. To overcome this problem one may use XML in conjunction with the GaudiObjDesc package to describe the data-objects. There were two key issues which led to the development of this description language:

· The core information of a data-object lies in the members of the class, most of the rest is redundant information which can be produced automatically around the members.· There is a lot of information which also must be provided, but which has a default-value in most of the cases.The information provided in the XML files can be used to produce not only the object information in the classes but also reflection information about the objects (see Section 12.10). Future releases may also produce, e.g., converters, or a description of the object in other languages.

As an example, the following XML code describes an MCParticle class:

All of the elements in this listing (eg. <class>, <attribute>, <relation>) have several attributes with default values (eg. for relations and attributes ” setMeth=’TRUE’ “), which don’t have to be mentioned explicitly. If one doesn’t want to use the default, the only thing that has to be done is to set the corresponding attribute to another value. There are also several hooks which can be applied eg. to define your own methods if they were not created automatically. The complete syntax of this description language can be found on the web at http://cern.ch/lhcb-comp/Frameworks/DataDictionary/.

Once a set of data-objects is defined, the XML file has to be saved to the xml directory of the package. The production of the C++ header files containing the object description can be automated by adding a line to the CMT requirements file of the package, as shown for example below:

document obj2doth LHCbEventObj2Doth ../xml/LHCbEvent.xmlAnother possibility is to produce the information by hand with the tools of the GaudiObjDesc package (eg. GODCppHeaderWriter.exe) and then compile it.

7.7.1. The class ID¶

The class definition on line 1 of Listing 7.4 contains an ‘id’ attribute. This class identifier is required if the objects of this class are to be made persistent. It is used by the data persistency services to make the translation between the transient and persistent representations of the object, ising the conversoin mechanism described in Section 14. For this mechanism to work, these identifiers must uniquely identify the class and no two classes may have the same identifier. The procedure for allocating unique class identifiers is, for the time being, experiment specific.

Types which are derived from ContainedObject must have a class ID in the range of an unsigned short. Contained objects may only reside in the store when they belong to a container, e.g. an ObjectVector<T> which is registered into the store. The class identifier of a concrete object container class is calculated (at run time) from the type of the objects which it contains, by setting bit 16.

7.8. The SmartDataPtr/SmartDataLocator utilities¶

The usage of the data services is simple, but extensive status checking and other things tend to make the code difficult to read. It would be more convenient to access data items in the store in a similar way to accessing objects with a C++ pointer. This is achieved with smart pointers, which hide the internals of the data services.

7.8.1. Using SmartDataPtr/SmartDataLocator objects¶

The SmartDataPtr and a SmartDataLocator are smart pointers that differ by the access to the data store. SmartDataPtr first checks whether the requested object is present in the transient store and loads it if necessary (similar to the retrieveObject method of IDataProviderSvc). SmartDataLocator only checks for the presence of the object but does not attempt to load it (similar to findObject).

Both SmartDataPtr and SmartDataLocator objects use the data service to get hold of the requested object and deliver it to the user. Since both objects have similar behaviour and the same user interface, in the following only the SmartDataPtr is discussed.

An example use of the SmartDataPtr class is shown in Listing 7.5.

The SmartDataPtr class can be thought of as a normal C++ pointer having a constructor. It is used in the same way as a normal C++ pointer.

The SmartDataPtr and SmartDataLocator offer a number of possible constructors and operators to cover a wide range of needs when accessing data stores. Check the online reference documentation [GAUDI-DOXY] for up-to date information concerning the interface of these utilities.

7.9. Smart References and Smart Reference Vectors¶

It is foreseen that data objects in the transient data stores can reference other objects in the same data store. This relationship can be described in the XML data description using the ‘relation’ attribute of the class definition, as shown on line 4 of Listing 7.4.

The current implementation of these relationships use ‘Smart References’ and ‘Smart Reference Vectors’. These are similar to smart pointers, they provide safe data access and automate the loading on demand of referenced data, and are used instead of C++ pointers. For example, suppose that MCParticles are already loaded but MCVertices are not, and that an algorithm dereferences a variable pointing to the origin vertex: if a smart reference is used, the MCVertices would be loaded automatically and only after that would the variable be dereferenced. If a C++ plain pointer were used instead, the program would crash. Smart references provide an automatic conversion to a pointer to the object and load the object from the persistent medium during the conversion process.

The XML code in Listing 7.4 will generate Smart Reference and Smart Reference Vector declarations as shown below:

The syntax of usage of smart references is identical to plain C++ pointers. The Algorithm only sees a pointer to the MCVertex object:

SmartRef offers a number of possible constructors and operators, see the online reference documentation [GAUDI-DOXY].

7.10. Persistent storage of data¶

7.10.1. Saving event data to a persistent store¶

Suppose that you have defined your own data type as discussed in section Section 7.7. Suppose futhermore that you have an algorithm which creates instances of your object type which you then register into the transient event store. How can you save these objects for use at a later date?

You must do the following:

· Write the appropriate converter (see Section 14)· Put some instructions (i.e. options) into the job option file (see Listing 7.6)· Register your object in the store us usual, typically in the execute() method of your algorithm.

In order to actually trigger the conversion and saving of the objects at the end of the current event processing it is necessary to inform the application manager. This requires some options to be specified in the job options file:

The first option tells the application manager that you wish to create an output stream called “DstWriter”. You may create as many output streams as you like and give them whatever name you prefer.

For each output stream object which you create you must set several properties. The ItemList option specifies the list of paths to the objects which you wish to write to this output stream. The number after the “#” symbol denotes the number of directory levels below the specified path which should be traversed. The (optional) EvtDataSvc option specifies in which transient data service the output stream should search for the objects in the ItemList, the default is the standard transient event data service EventDataSvc. The Output option specifies the name of the output data file and the type of persistency technology, ROOT in this example. The last three options are needed to tell the Application manager to instantiate the RootEvtCnvSvc and to associate the ROOT persistency type to this service.

An example of saving data to a ROOT persistent data store is available in the RootIO example distributed with the framework.

7.10.2. Reading event data from a persistent store¶

Suppose you want to read back the file written out in the previous section. To do this, your job options would look something like those described in Section 5.4.3.